In May, I’ll be releasing a new body of work relating to the 800th birthday of the Magna Carta. Through it, I’m looking at the developing relationship between law and citizens. This work will be on display at the Alameda County Law Library in May and early June.

To introduce this discussion, I would like to share with you the thought provoking work of artist Heather Green. I had the privilege of speaking with her about her work last week.

Heather Green’s show, Victims and Villains, shown at the Kruger Gallery in Chicago in February 2015, featured four larger than life oil on wood panel portraits, and a series of graphite, charcoal and ink drawings with tweeted texts carefully cut out from the drawing.

The large portraits are painted from mug shots that were in the public eye, including George Zimmerman, Marissa Alexander, Austin Smith Clem, and Darren Deon Vann.

Green has studied these mug shots with tremendous depth and tender attention to get at the human that seems absent from the published photograph. This is especially apparent in the portrait of Marissa Alexander, a mother who was sentenced to twenty years in prison for firing a warning shot into the wall, claiming in trial it was to let her abusive husband know she would defend herself if he attempted to follow through on his threat to kill her. (His abuse record was well documented and she had no prior criminal record.) In Alexander’s mug shot, her eyes have a carefully opaque veil. However, the artist, by immersing herself in the mug shot’s gaze, and carefully studying the many other public images of Alexander in other settings, is able to coax out a person behind that deeply guarded stare.

As the gallery aptly points out, a mug shot is a dehumanized image of the accused, recorded, archived, and often shared with the public, branding the person as “criminal” before a conviction takes place in court. As I reflected on this, it raised a question about the meaning of due process within our judicial system. The Fifth Amendment says no one shall be deprived of “life, liberty or property without due process of law.” “Due process,” is the requirement that a person’s rights must be respected. When a person is presented to the public in this subhuman manner, have his or her rights been violated? The Fifth Amendment, with all its hallowed language, does not protect a right to remain human.

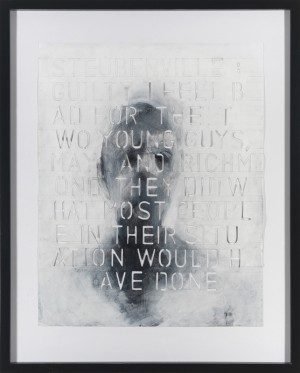

The second body of work, #yesallwomen, references actual tweets responding to the Steubenville rape case in 2012, in which a sixteen-year-old had been drinking with other teens at a party, passed out, was stripped, molested and raped by two high school football players, all of which was recorded, texted, and posted through the cell phones of the other teens at the party. The two accused teens were convicted the following year. In each of Green’s pieces we see a ghostly, nondescript head in charcoal, pencil, and ink. Superimposed over the blurred headshot, Green has painstakingly cut the tweet out of the portrait, character by character, a deft visual representation of the cutting remarks voiced against the victim. Color is absent from these pieces, and only the foggiest hint of a human being is depicted in the ephemeral profile-photo-like headshots. The overall effect is simultaneously beautiful and repugnant.

Some of the accused of this exhibition were convicted of the most fearful crimes. Some received very little time in relation to their offense. Others were convicted of a comparably small offense and received a great deal of time. George Zimmerman was acquitted under the Stand Your Ground law, despite having killed, and having had a past criminal record. Marissa Alexander was convicted under the same law despite having hurt no one, and having had no criminal record. Green’s frustration with society’s failed attempts at just outcomes is a strong undercurrent running through this exhibition and her work, which is conscientiously wrought, beautifully executed, and thoughtfully displayed.

Share: