Last Saturday, I arrived at a crowded gallery at the Richmond Art Center to break donuts and sip caffeine with the Breakfast Group. (Ok there was healthy food too, but breaking salad didn’t sound as poetic.) The exhibit had been rearranged from the night of the artists’ reception. The alcove now showcased the works of mixed media printmaker Robert Simons and metal sculptor Joseph Slusky, spotlighting the two artists would be speaking to the group that day. People who were eating and chatting when I arrived soon moved to chairs arranged around the alcove for the artist talks.

The RAC is exhibiting “Jive and Java with the Breakfast Group Artists” this spring. During the exhibit, the artist members of the Breakfast Group are conducting their weekly breakfasts, which are usually invitation-only affairs, in the gallery and open to the public. Fifty years ago, UC Berkeley art professors, including American Constructivist painter and sculptor Sid Gordin, and pioneering member of the Bay Area Figurative School Elmer Bischoff, began meeting over breakfast to talk about art, ideas, and life. The Group has grown to include faculty, alumni, and friends drawn in to sustain a weekly ritual of news, art, and breakfast.

From a long-standing roster, thirty artists are represented in the exhibition at the Richmond Art Center. The works displayed cross art movements and genres, favoring dedicated individual artistic visions and manifestations of lifelong careers.

The Artist Talks

I selected Simon’s and Slusky’s talks to attend and write about because I felt their work shared the most resonance with my own. Both artists use color boldly. Simons combines mixed media and printmaking, as do I. Slusky’s welded metal sculpture has a gritty urban quality which, though is not directly related, feels connected to my West Oakland studio neighborhood, a setting which has given inspiration to some of my own work.

Robert Simons and Joseph Slusky also have a good deal of resonance with each other. Consequently, the two have exhibited together before, and Slusky wrote the text for Simons’ recent catalog for the Kennedy Art Center.

Robert Simons

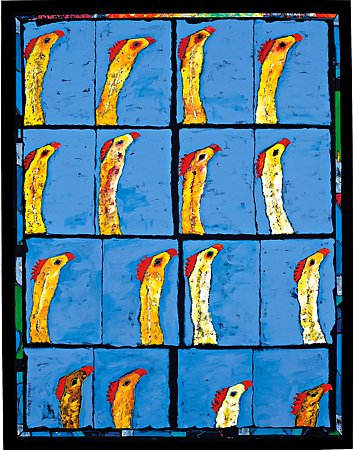

39.25×30″ oil & acrylic (photo courtesy of the artist)

Robert Simons uses modest subjects in profound ways. His recent bodies of work include children’s toy animals, such as a rubber chicken or duck, portrayed to emphasize simultaneous vulnerability and dignity. “How so?” you well might ask. For example, in the work “The Orderly Departure” 12 chicken necks and heads are featured in each of 12 separate panels. The birds are beautifully colored with their heads held high, despite immanent demise.

Simons early works, black and white intaglios, suggested something ominous, dark. As he shifted into serigraphy, his themes intensified into primordial fire, destruction, and rebirth: titanic subjects, which he portrayed likewise with bold, forceful color.

When Simons moved into mixed media, he began working with the stated concepts of vulnerability and nobility, an event that also seems to have coincided with growing his family. This struck a nerve with me. I don’t know Simons’ personal reflections at the time, but for myself, the births of my own children have naturally come with a whole host of responses to their vulnerabilities – from practicalities such as “baby-proofing” the home to philosophical inquiries such as imagining our century’s cruelest villains as guiltless and needy infants.

Indeed Simons explorations into vulnerability and nobility go hand in hand, for when one engages in the act of protecting oneself, one seems to lose a degree of nobility. History and current events show this. To take an analogy from Simons’ works, some of which address the Holocaust, history shows us people who wanted to cease the real pain of an impossible economy, who turned to a leader who promised to destroy their vulnerability. And they did –with supremely horrific results.

A willingness to accept our own vulnerabilities, and leave them there in the open, is a key face of our integrity. And what happens when given an impossible choice? Do we protect ourselves, watch the people’s every word for threats, send out drones, or as Plato suggested, “kill the artists?” Do we forsake our nobility for our own protection, or walk to our deaths with integrity, with the chickens? Simons doesn’t answer whether there is a middle ground. That is for us to determine.

Joseph Slusky

steel & acrylic lacquer paint 43″H x 38″L x 32″W (photo courtesy of the artist)

Slusky also uses the toy as “a vehicle for entry into other issues.” He grew up in LA near the La Brea tar pits, with childhood memories of playing in the driveway for hours with small metal toys from the local farmer’s market. Today he likens his work to “the imagination fossilized,” and speaks of his sense of play as he welds his sculptures.

But his creations are not the work of a child. Their color and acrobatic form defy the staid authority of drab beige and gray of institutions, instead offering energetic liveliness that is solid, heavy, and enduring, with an element of grit.

When Slusky began sculpting metal in his college days, he was making things fast. By the next day, the object wasn’t holding his attention anymore and he was on to the next sculpture. He then sought to determine how to create something with visual longevity. He employed a couple of strategies: whatever would come to mind, he would act on it on the present piece rather than a new one; and he began using a plastic filler to seamlessly connect his metal components, creating fluid forms that appeared as solid metal. His work gained complexity and a dance-like poetic form that has stayed with him throughout his career.

The shape and volume of the negative space are as important to these sculptures as the form and line constructed in the metal. So, too, are subtractive techniques as integral to Slusky’s work as additive ones. Once he has finished welding a form, Slusky applies colorful coats of car lacquer, allows it to dry, and then covers the whole sculpture in black lacquer. Next he sands and buffs until the color is again revealed through the black (all the while listening to poetry). But not all of the black is removed and other marks are made in the process of removing paint.

Slusky notes that the metal sculptures are the ephemeral and ethereal human imagination transformed into something immutable. They are of a substance harder, heavier, and more durable than our fragile selves.

More to See and Hear

There are still five more discussions open to the public at the Richmond Art Center. They are free, from 11-1. Bring a breakfast goodie to share if you’re able to, but definitely sit down to talk, ask questions, and listen:

Mar 29 – Sculptor Patricia Bengtson Jones & Painter Edythe Bresnahan

Apr 5 – Painter & Drawer Jan Wurm

Apr 12 – Painter Katie Hawkinson

Apr 19 – Mixed-media artist Robert Simons & sculptor Joe Slusky

Apr 26 – Painter Donna Fenstermaker & sculptor Stan Huncilman

May 3 – Painter Carol Ladewig

May 10 – Mixed-media artist Guillermo Pulido

May 17 – Watercolor painter Loren Rehbock

May 24 – Painter Nancy Genn

Workshops are also being offered by members of the Breakfast Group. See the Richmond Art Center website for details

Share: